Peek into the past on Lower St James’s St.

By Roger Frost

A couple of weeks ago I stated that I had some new ideas for Peek into the Past. This is the first of a series of articles in which we will take a look at Lower St James Street, not through my eyes but through those of an anonymous writer who put his thoughts on paper some fifty years, or so, ago. He does give us a few clues as to who he might have been but, as yet, I have not been able to resolve that question.

The reason for doing this is that the Council, Mid Pennine Arts, the Burnley Campus of the University of Central Lancashire, and other partners, are involved in the implementation of an Action Zone for Lower St James Street. I have been asked if I would put my historical knowledge at the disposal of the students, and I have agreed to do so.

What I intend to do, over, the next few weeks, is to make available aspects of the reminiscences of the individual mentioned above. It might be possible to discover who he might have been but I have checked what has been written and, so far as I can determine, the reminiscences are not without a ring of authenticity.

For example, I have wondered, for some time, why it was thought necessary, when the Victoria Opera House opened, to name it the Victoria Assembly Rooms and, later the Victoria Assembly Rooms & Opera House. The author, as you will find out, gives a very good reason, but first let us start with saying something about the document itself. I have used the writer’s words but, when necessary, I have changed the grammar and combined, or split, paragraphs, to make the document clear to the present-day reader. Parentheses have been used to explain details, when necessary. I hope that you find the document as interesting as I have.

The writer of the document starts, “I have been asked to give some reminiscences. I suppose, when one is 79 one is entitled to be reminiscent occasionally. I shall be obliged to speak generally, in the first person, and I shall introduce my grandmother, and others, to use, in a sense, as people on whom to hang many of my remarks”.

The first comments tell us when the writer was born and a little about the world at the time. “I was born in the year 1870. The year of the Franco-Prussian War, when British sympathies were with the Prussians. (The Prussians were Germans). A Liberal Government (led by Gladstone) was in power with a cabinet one half of which was composed of Peers. Compulsory education was introduced this year (1870) – compulsory but not free. We still had to take our weekly coppers to school, the amount varying according to the Standard one was in.

“The Ballot Act was now in preparation, and passed in 1872, but the agricultural labourer was yet without a vote. The Income Tax this year, 1872, was 5d in the pound. (.2p in the pound today). Our local Borough Rate, plus the poor rate, was 3s 3d in the pound.” (These latter two payments were known as “The Rates”. There is no Poor Rate today and the Rates have been replaced by the Council Tax).

The author then refers to more local matters. He points out that, “One heard little about hygiene in

those days. Not 10% of the houses in Burnley had a bathroom”. However, the town itself was expanding rapidly, in the 1870’s. “Long rows of houses of all classes, and in all parts of the town, were being built, cheaply, and none, or very few, provided with a bathroom”.

Under a bed, in most houses, would be found a wide, shallow circular metal bath. On bath nights, this would be brought out and placed near the hearth, in front of the fire, and filled with water reaching to the ankles, where washing would take place. Everyone in the household would, with as much privacy as possible, wash, but emptying the bath afterwards, without making a mess, was a ticklish job which, perhaps, gave rise to the adage, “Don’t throw away the baby with the bath water”.

The point is made that there was no hot water on tap. It was got from the kitchen range boiler. Sanitary arrangements were very primitive. There were very few water closets, but matters were improving. The writer comments, “Instead of the tank, which had to be emptied by a scoup, a cistern, or container, was installed.

“The Night-Soil men, a euphemistic term, were employed every morning from 3am to 6 o’clock on emptying these cisterns”. (So far as I know little has survived from this operation which was carried out across the town. I don’t think, as implied above, that every house was visited on a daily basis, but the night soil men, rose early in a morning to carry out their essential, but very unpleasant, work.

Each house had a small building, in the back yard, where human waste, sometimes mixed with soil, was deposited. Iron grates, on the back street, gave access to the night soil which was taken away and often used as manure by farmers. We are fortunate that an image survives showing night soil me at work. It was published, in the “Burnley Express”, in January, 1988, and it is thought to be of Nelson. I have included a copy with this article).

Next week I will add to these general reminiscences, but, now, I’d like to see what our author wrote of St James Street, but a word, or two, of caution about St James Street.

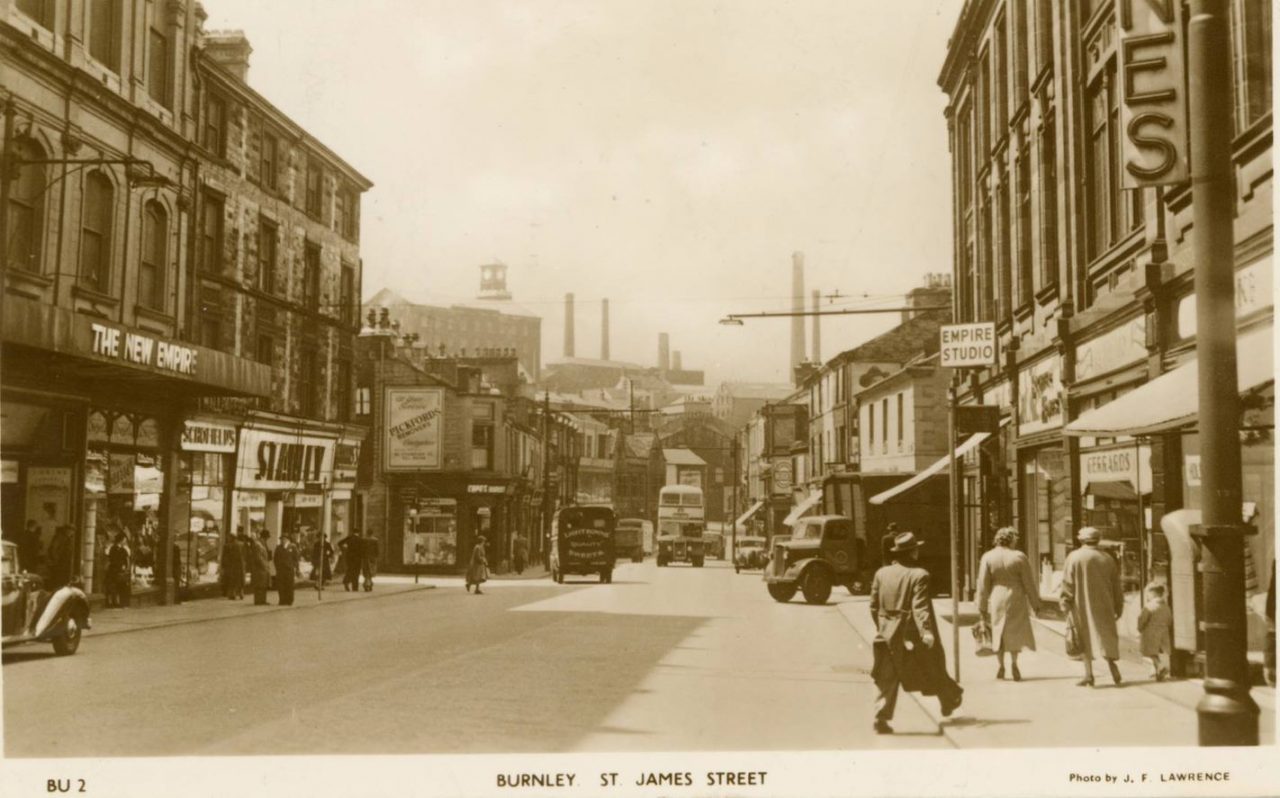

As you will know St James’ Street is Burnley’s main street. A lot of it is pedestrianised, these days, but, in the past, the street was very busy for the whole of its length. The street was a continuation of Church Street and ran from Hall Street and Yorkshire Street, in the east, to the river Calder, in the west. After the bridge, over the river, the streets were Westgate, Sandygate and Caldervale Road.

It should be remembered that parts of St James Street had different names in the nineteenth century. Starting, at the eastern end of the street, where the low numbers are, the first stretch of the street was known as Blucher Street, after the Prussian general who fought with Wellington at Waterloo. The name St James Street was used from about the junction with Parker Lane through to the junction with Hammerton Street and Curzon Street. After that the street was known as Goodham Hill and Cheapside. The latter name was given for the part of St James Street below Cow Lane.

The Action Zone is concerned with the present-day St James Street, west of Hammerton Street and Curzon Street. In other words, we are concerned with Goodham Hill and Cheapside. Unfortunately, the origins and meaning of Goodham Hill are unknown, but there was rising land from the Calder, so

there may have been something of an incline, or slight hill, in the road at this point.

Goodham Hill extended to at least Brown Street, on the right, or possibly to Cow Lane, on the left. The use of “good”, in a place-name, is usually a reference to a particular individual’s personal, or fore, name, but that is not helpful here.

On the other hand, Cheapside is a reference to a market, from the Old English, “ceping”, market. |It is known that markets were held in this part of town in the nineteenth century, one of them being the Victoria Market, on the site of the building that, later, became Woolworths, at the corner of Hammerton Street and St James Street.

This market had nothing to do with Burnley’s Ancient Market which, for the early part of the nineteenth century, had operated at the junction between St James Street and Manchester Road. The markets of Lower St James Street, as it is now known, were illegal in the sense that they infringed the rights that went with the Ancient Market. I know of at least two such markets.

So, what does our author say about Lower St James Street? “My maternal grandparents had a draper’s shop – long since pulled down – opposite to where the Victoria Theatre stands today. Next door was Nowell’s butchers. This was a large shop where a big business was done. There were cellars under the shop and one extended under my grandparents sitting room.

“As a boy I have stood in the back yard and, looking through a grid, watched the men, turning out of a machine, long lengths of sausages and polonies. Close to the machine, were heaped up, piles of hot mince, seasoned meats, ready for the machine. The warm scented aroma of the meat rose and pervaded the back yard and entered the kitchen of my grandparents. Adjoining was the slaughter house.

“As a boy of seven, I have stood at the open door and seen the cattle pole-axed and the sheep and pigs (knifed) and the carcasses gutted and dressed. I don’t think a boy of seven is very sensitive. At any rate, I looked on this slaughtering little perturbed and as quite in the natural order of things. The heavy smell of the slaughter house also entered my grandparent’s kitchen”.

According to the 1872 Commercial Directory, William Nowell’s butcher’s shop was at 19, Goodham Hill, which would have been between Bethesda Street and Brown Street. He lived at 23, Hargreaves Street. In 1872, there was a linen and woollen draper at 21, Goodham Hill, which was operated by Hugo Cragg. What the writer of the reminiscence has to say about the location of the businesses can be born out, so far as the butchers and the drapers. It is likely, that the grandparents of our author were Mr and Mrs Hugo Clegg.

The other firm mentioned is Heaton’s chemists. “Next door, but one to Nowell’s was Heaton’s chemists. At the back of their premises were casks and containers of paraffin and other very pungent oils. These acute and distinctive scents also entered my grandparent’s house. Now, I don’t think that my grandparents ever thought that they had any cause to complain. It was accepted as inevitable and quite in the order of things”.

The shop was run by Martha Heaton, as a chemist and druggist, of 15, Goodham Hill and these details fit in with our author’s description. Later, the name Goodham Hill was dropped and St James

Street was used for the full length of the street. Martha Heaton & Son, druggists, appear, in the 1883 Commercial Directory, at 121, St James Street.

The individual who wrote the reminiscences makes comment about his grandparent’s shop. “My grandparent’s shop had its own characteristic odour from scores of rolls of cloth, mainly wool and cotton. Finally, from Tunstill’s Mill across the road, and where the Victoria Theatre now stands, came the smell of raw cotton in process and of warm lubricating oil”.

From these reminiscences we find out a little about what it was like to live in Lower St James Street. We have mentioned a butcher’s and a chemist shop, both of which appeared to operate with little regulation. At the time, the operation of a large slaughter house, directly besides where families were living, aroused little comment, and neither did the location of containers of highly inflammable paraffin, in the back yard of the chemist shop.

The odours and smells from the draper’s shop and Tunstill’s Mill were nothing when compared to these, but we must remember that Lower St James Street had dozens of other shops. They included businesses where owners – other butchers, several tripe dressers, even confectioners, eating houses and a fish-monger, where there would have been other opportunities to cause offence.

However, as our writer states, Goodham Hill and Lower St James Street were about to change. Next week I will tell you how the building of a proper theatre, Burnley’s first, changed Lower St James Street for ever.